Existential types and data abstraction

Lately, I have been encountering interesting pieces of Haskell code full of various type-related concepts: GADTs, existential types, type families, etc. Now I am trying to face them one by one and grok as much as I can.

I think I have managed to understand several interesting ideas in existential types which I’d like to share with others.

This post is based on literal Haskell code, which can be downloaded (and run in ghci) from Github.

Example of type declaration

Let’s start with an example of existential type. I will use some pseudo-code notation which will be transformed into usual Haskell (albeit with certain GHC extensions) later.

T = ∃a. { x :: a

, f :: a -> Int

}We define a new type T. It has a type variable a, which is existentially quantified (this is expressed with a quantifier ∃, exists). Also we have a record with two fields: a value x and a function f.

Existentially quantified means that there exists some type a, which we may choose when we construct a value of existential type.

To understand this better, let’s see how we construct and use values of existential types.

Value construction

Consider several example values of type T defined above (i.e. possible elements of T):

{ x = 1, f = \n -> n + 2 } (a = Int)

{ x = False, f = \b -> if b then 1 else 0 } (a = Bool)

{ x = 'c', f = \c -> ord c } (a = Char)Existentially typed values consist of two components:

- a type component

- a term component

The type component is called hidden representation type or witness type (a tribute to mathematical logic). The term component in this example is a record with two fields.

Note an interesting thing: even though we have chosen a to be different in every example, all three values belong to the same existential type T.

Well, while looking on the three examples above, we have seen how values of existential types are constructed: we choose the representation type a and values for x and f fields are chosen accordingly.

Value usage

Now let’s think how we can use these values. We may use pattern matching to deconstruct the value:

use (T x f) = ???What is the type of x? We don’t know and can’t know: it is held abstract, since we could have chosen any type while constructing the value, as you have seen in the previous section.

The only thing we know here is that the very same abstract type is present in the type of f (a quick refresher: x :: a, f :: a -> Int), so that f and x are composable: we can apply f to x to obtain an Int:

use :: T -> Int

use (T x f) = f xIn fact, this is all we can do with this value.

So we have a hidden representation type and several allowed operations, hm… A-ha, this reminds me a very well-known concept! Indeed, it is quite similar to the familiar idea of abstract data types: we are hiding implementation details and provide only a certain set of allowed operations, so that later we can freely change the implementation and no one will notice.

We have just seen a connection between existential types and abstract data types, which, I believe, is the most important aspect of existential types.

More realistic example (slightly)

In the previous example, all we could do was to get an Int and it’s not very exciting – we could just have used Int directly instead! Let’s see one more example, this time written in Haskell. Certain questions will arise after looking on the code below. I hope I’ll answer most of them in the rest of the article.

Meet the Counter!

{-# LANGUAGE ExistentialQuantification #-}

data Counter = forall a. MkCounter

a -- new

(a -> a) -- inc

(a -> Int) -- getHere we have a constructor with three fields, since our counter supports three operations: new creates a new counter, inc increments a counter by one and get retrieves the current counter value. Representation type a remains hidden and abstract, note that we don’t have it in the left hand side of the type definition.

Let’s implement two different types of counter, i.e. let’s construct two values of Counter type. For the first of them we choose a to be Int:

intCounter :: Counter

intCounter = MkCounter

0 -- new

(+1) -- inc

id -- getAnd let’s use a list type for the second one, somewhat arbitrary, but why not? We increment the counter by adding a unit element to the list and we get the counter value by evaluating the length of the list:

listCounter :: Counter

listCounter = MkCounter

[] -- new

(() :) -- inc

length -- getNow let’s use it:

test :: Counter -> Int

test (MkCounter new inc get) = get $ inc $ inc $ new*Main> test intCounter

2

*Main> test listCounter

2See? We pass as an argument a concrete implementation of abstract data type (which is in the same time just a value of existential type Counter), therefore providing our test function with three operations on counters, which may be composed in certain ways.

Types assignment

It’s interesting to see what types are assigned to the variables new, inc and get. Each time when we pattern match against a constructor with existentially typed variable inside (a in our case), the type checker uses a completely new type for a, which is guaranteed to be different from every other type in the program, so that it cannot be unified with any other type variable. For example here:

test (MkCounter new inc get) = ...the type-checker sets a to, say some unique c1 and therefore assigns the following types to new, inc and get variables:

new :: c1

inc :: c1 -> c1

get :: c1 -> IntType classes and constrained existentials

Now let’s take a look at the classical first example of existentials.

Let’s say we want to have a list of values of different types, and each of them is an instance of Show, so that we can print them all. No problems:

data ShowBox = forall a. Show a => ShowBox a

instance Show ShowBox where

show (ShowBox v) = show v

boxList :: [ShowBox]

boxList = [ ShowBox 1

, ShowBox False

, ShowBox [1,2,3]

]

testShowBox :: IO ()

testShowBox =

mapM_ (\sb -> putStrLn $ show sb) boxList*Main> testShowBox

1

False

[1,2,3]Voilà! In fact, having Show a constraint is equivalent to having an additional show operation in our data type (similar to inc, get we saw before):

data ShowBox2 = forall a. ShowBox2

a -- value

(a -> String) -- show operation

boxList2 :: [ShowBox2]

boxList2 = [ ShowBox2 1 show

, ShowBox2 False show

, ShowBox2 [1,2,3] show

]

testShowBox2 :: IO ()

testShowBox2 =

mapM_ (\(ShowBox2 v sh) -> putStrLn $ sh v) boxList2*Main> testShowBox2

1

False

[1,2,3]Here we are passing around show explicitly, which is certainly less convenient, than just setting a Show constraint while declaring the data type.

Hiding the type in such a way, by using an existential type along with a constraining type class is a popular approach (it is used for example in the famous xmonad window manager), but this is considered a Haskell “antipattern” by some people (because sometimes we can replace it with a simpler approach). For more details, see this interesting post.

Why “forall”?

You have probably noticed that we used forall in the Haskell code while working with existentials, why so? exists seems to be more appropriate, no?

Let’s see why it works.

data T = C1 (exists a. F a) -- what we wanted to write, not valid Haskell

data T = forall a. C2 (F a) -- what we wrote in valid HaskellHere, F is some type constructor that uses a.

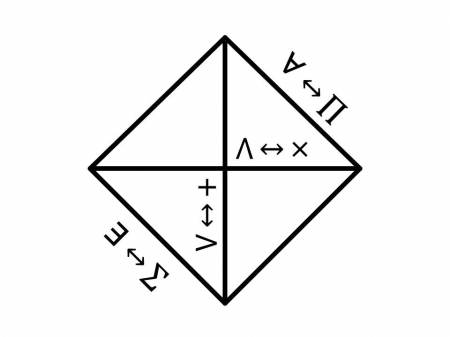

It turns out that we can show equivalence of these definitions. Curry-Howard isomorphism to the rescue!

I won’t go into details here (and frankly, I’m far from being an expert in this area), but Curry-Howard correspondence demonstrates a beautiful connection between type theory and intuitionistic (or constructive) logic, where types corresponds to logic propositions, and values corresponds to proofs of these propositions.

Let’s write types of constructors:

C1 :: (exists a. F a) -> T

C2 :: forall a. (F a -> T)This corresponds to the following propositions in first-order logic, as stated by Curry-Howard isomorphism:

(∃a. F(a)) -> T

∀a. (F(a) -> T)It’s an easy exercise to prove their equivalence, i.e. to prove the following:

(∃a. F(a)) -> T ⇔ ∀a. (F(a) -> T)You can see an example of the proof using so-called sequent calculus (even with Coq source for curious!) in this article of Edward Z. Yang, who also mentions this formula while talking about existential types.

If you want to learn more about Curry-Howard isomorphism, many people recommend Lectures on the Curry-Howard Isomorphism by Morten Heine B. Sørensen and Pawel Urzyczyn.

Existentials and currying

Let me show you one more unexpected and beautiful idea. As you probably remember a value of existential type is a pair of a term and a type:

value of ∃a.F(a) = (Type, term of F(Type))where F is a type constructor.

But what is the interpretation of universally quantified type ∀a. F(a)?

We haven’t talked about universally quantified types in this article, but a value of such type can be thought of as a mapping of any type a to a term of type F(a), or just a function from type a to a value of F(a) type, i.e.:

value of ∀a. F(a) = Type -> term of F(Type)A list might be a good example of a universally quantified type:

data List a = Cons a (List a)

| NilSo, existentials are pairs and universals are functions. Now taking this interpretation into consideration let’s rewrite types of our constructors from:

C1 :: (exists a. F a) -> T

C2 :: forall a. (F a -> T)into:

C1 :: (S, value of F(S)) -> T

C2 :: S -> (value of F(S) -> T)S is some type here. We substituted values of existential and universal types according to our pairs/functions interpretation.

And now we can see that C1 to C2 can be easily transformed one into another using currying! Let’s rewrite it once more for clarity:

C1 :: (S, v) -> T

C2 :: S -> (v -> T)

curry C1 = C2Beautiful!

As we can see, these two constructors have isomorphic types and therefore we can express existentials using universal quantifier forall, which is exactly what GHC does.

Existentials in GHC

To use existentials you will need ExistentialQuantification pragma in GHC. Also, note that forall keyword is necessary while declaring existentials, you can’t omit it, i.e. you can’t write this code:

data Box = Box aassuming that a is existential just because it’s not present in the left hand side of the declaration. Allowing this kind of implicit existentials would have probably increased amount of unexpected errors with tricky messages (when you just forgot to mention a variable in the left hand side of the declaration).

Other proposals for existentials syntax are described on Haskell Prime wiki.

Conclusion

Existential types are quite an interesting concept, we may use them to abstract away types, hide implementation details and even to simulate objects, message passing and something like dynamic dispatch. It would be cool to write more about it, but this post has already become too large.

Sources / Reading List

While trying to grasp existential types and preparing this article, I’ve used many different sources, including Benjamin Pierce’s “Types and programming languages” (which greatly influenced this article), Haskell wiki, Stack Overflow answers, various articles and blog posts, I would like to mention the most valuable and interesting sources here:

TAPL, Chapter 24 “Existential types”

Haskell wiki book, “Existentially qualified types”

GHC manual, “Existential quantification”

Stack Overflow questions and answers:

Posts:

Articles:

Exercises

It may be instructive to implement stack data structure or complex numbers as an abstract data type with the help of existentials.

Try to implement and use Counter with type classes instead of existentials. Are there any major differences?

If you liked my post, consider subscribing to my feed